One important concept in personal finance is financial independence. You are financially independent when you no longer need to work for a wage in order to support your standard of living.

One important concept in personal finance is financial independence. You are financially independent when you no longer need to work for a wage in order to support your standard of living.

Sound awesome?

How do you get it?

Well, you save enough money to create a portfolio of stocks and bonds which you can live off of instead of your wage. Turns out the money required to replace working for a living is quite substantial…

According to the trinity study withdrawing 4% of your starting portfolio and adjusting the figure upward for inflation every year would result in a hypothetical starting portfolio lasting at least 30 years in 95% of cases. In most of those cases, the portfolio ends up larger in real terms than you started with, ready for another 30-year stint.

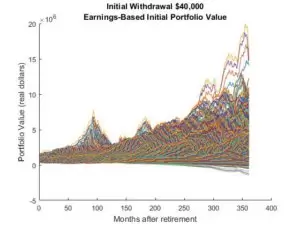

For this reason, you are generally considered to be financially independent once your portfolio is 25x as big as your annual living expenses. This is to say you are financially independent when you could choose to retire and not have to change your standard of living. I confirmed the trinity studies numbers by taking Robert Shiller’s inflation adjusted S&P 500 data (going back to 1870) and adjusting a hypothetical portfolio on a monthly basis for withdrawals and dividends as well as portfolio growth over a 30 year period. I repeated this, starting the hypothetical portfolio at each year starting at 1870. This gave me over 100 runs which I plot below:

These are all of the portfolios runs just plotted on top of each other. I found a 98% success rate with the 4% rule. I’m not quite sure what results in the discrepancy. You can see that on the left side of the graph each portfolio starts at $1,000,000. On the right side, you can see that results are very different. Sometimes you end up with $20,000,000, sometimes you go bust and end up with nothing. As a prospective retiree, this chart looks pretty scary.

You have to save $1,000,000 just to be able to spend $40,000, and then you still go bust a bunch!

Sure sometimes you end up with way more money, but you’ll probably feel pretty stupid sticking hard to that $40,000 budget, then dying with $20 million in the bank. The number of busts are scary, many prospective early retiree’s try to be conservative they switch over to a 3% rule. This means that to spend $40,000 they’ll have to save over $1.3 million! This could mean adding a substantial amount of years to your working life. It could possibly mean that you don’t mind earning an extra house worth of money before retirement, but hey, then you don’t really need to worry about most of this.

Improving on the 4% rule

What if, rather than viewing our portfolio as a pile of money, we viewed it as ownership of operating businesses? If you owned a car wash chain, and every year the chain earned $60,000 in profit, how would you calculate the amount that you could spend year to year?

Would you think, “well I could sell the car wash for $1,000,000 and 4% of $1 million is…”

You’d probably just say, “I earn $60,000 annually, I should save some to grow the chain, and provide some cushion against bad years. I can probably spend like two-thirds of this. So I can spend $40,000 annually.”

You should look at your stock portfolio the same way!

Why?

When you own a stock you are really just a fractional owner of an underlying business. You should act like it. Don’t base your retirement on the size of your portfolio, base it on the accounting earnings of the underlying businesses!

Introducing the 2/3rds rule:

Let’s assume you have a portfolio consisting only of the S&P 500. To apply our above rule, we decide that we’re financially independent once we hit a specific dollar value of accounting earnings. Since we want to spend $40,000, we need $60,000 of accounting earnings from the S&P 500. (2/3rds of $60,000 is $40,000).

One “share” of the S&P 500 earned ~$16 in 1985. Therefore, in order to have $60,000 in earnings from the S&P 500 we’d need 3750 “shares” of the S&P 500. This isn’t necessarily easy as it sounds, as one of these “shares” cost $180 at the 1985 index level, this means that you’d need about $675,000 to retire based on this rule. That’s a substantial difference than the 4% rule which would require $1,000,000.

It isn’t a free lunch, however, because when the price per dollar of earnings is higher you would need more to retire than the 4% rule would indicate. If you decided to retire in January of 1999, S&P earnings were $38, thus in order to have $60,000 in earnings you’d need 1579 shares of the S&P 500. Given that the index level at that time was 1,280 that would imply that you’d need a portfolio over $2,000,000, twice the level that the 4% rule would predict.

So how well does the 2/3rd’s rule actually perform? I repeated the same study, only initial portfolio levels were set for constant accounting earnings ($60,000) of the S&P 500.

There is more spread in the starting portfolio values (on the left) compared to the previous plot. This is to be expected, the original plot started each run at $1,000,000, in this case, we start each run at a variable portfolio size based on the trailing earnings of the S&P 500 for that month.

What’s more interesting is that there is less spread on the right end of the plot! The highs are lower and the lows are higher. This indicates that the result for the prospective retiree is somewhat less random if they base their retirement on accounting earnings rather than portfolio size. The success rate using this method of retirement, 1% better than the 4% rule. While I’ve been unable to reproduce the trinity study values precisely, I conclude that somewhere between 20% and 50% of the portfolio failure events that would have happened if you followed the 4% rule in a random month sometime over the last 130 years would not have happened if you were following the 2/3rds accounting earnings rule.

This isn’t the only benefit. By applying this rule, not only does your portfolio fail to carry you through a 30-year retirement more rarely, you also need less money on average to retire. Following the 4% rule requires a starting portfolio size of $1,000,000 every time, regardless of the underlying earnings of the S&P 500. Following the 2/3rds rule required only $800,000 on average. Sometimes, you do have to accumulate more money, because valuations are high and each dollar invested doesn’t buy you much in the way of earnings (like in 1998, or present day), but on average you can accumulate substantially less money and still retire with a greater level of safety.

Adam Woods is a physicist. His research interests include building software to run and build geomagnetic models. Adam got interested in personal finance in the great recession when it became obvious an interest was necessary.

After harassing his friends and family (and a short intervention) he took to the web where he blogs about finance, investment, politics, and economics.

Adam is currently located in Boulder, Colorado where he can generally be found hiking, biking, or running a D&D campaign. He can also be contacted at adamwoods137@gmail.com.

Anything that helps make retirement earnings safer sure can’t hurt.

“Financially independent once your portfolio is 25x as big as your annual living expenses”…Well I’m not there yet 😉